Where do Asian Accents Come From?

December 15, 2019

There is a certain persistent stereotype that Asians cannot say the letter “l”. But which l? Velar? Dental? Voiced or unvoiced? And where in Asia — the most linguistically diverse continent in the world, home to over two-thirds of all the world’s languages, each with their own linguistic inclinations — do these accented speakers-of-English come from?

According to Ethnologue, there are more than 1000 non-extinct languages in the world right now. As comedian Trevor Noah once said, accents can be thought of as someone speaking a foreign language with the rules of their native one. In the case of accented speech, we deal with the rules of phonology and phonotactics: the way we make sounds and the rules by which they are arranged in any given language. Let’s first take a dive into some of the basic rules of phonology.

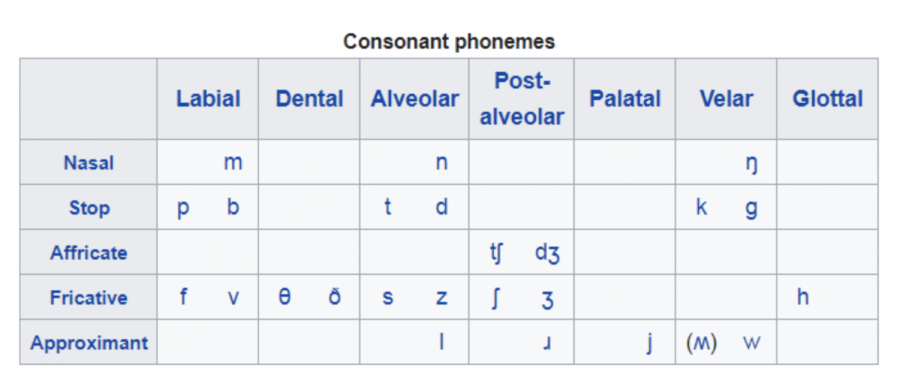

In the most general sense, phonology is the cataloguing and study of different sounds — vowels and consonants. For consonants, there are 3 major factors to consider: place of articulation (where in the mouth the tongue is placed), manner of articulation (how the tongue is placed), and voicing/nasalization (whether or not the vocal cords are vibrating or if air is passing through the nose). There are secondary factors as well, such as whether or not the consonant is aspirated (if there’s a puff of air afterwards), labialized (lips are rounded during articulation), or palatalized (middle of the tongue is raised to form a “y” sound).

In English, there are 7 major places of articulation, or where you put your tongue or lips when speaking. Dental means your tongue is between the teeth (like the “th” in “thin”). Labial means using lips (like the “p” in “pet”). Alveolar means that the tongue placed on the ridge in the mouth behind your teeth (like the “t” in “top”). Palatal means the tongue is right behind the alveolar ridge (like the “y” in “yes). Velar means the back of the mouth (like the “k” in “king”). Glottal means using your glottal flap — avid students of Biology will remember that this is the flap above your bronchus; English has only one example of this: the “h” in “hat”. There are, of course, many more places of articulation; English just has these 7.

There also exist differences in manner of articulation between consonants. Nasals are when air passes through the nose; stops are sounds where airflow is blocked completely (like the “d” in “door”); fricatives, where airflow is tightly constricted (like the “f” in “fire”); affricatives, where a stop and a fricative are articulated simultaneously (like the “ch” in “chair”); liquids, where the tongue forms a partial blockage (like the “r” in room); and approximants, where airflow is only somewhat constricted (like the “w” in “wet”). English only has two liquids: /l/ (the “l” in “look”) and /ɹ/ (the “r” in “rook”).

Above is the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) chart for English. Phonetic sounds are placed between forward slashes. You will see that although some phonetic symbols correspond directly with the English version of the letter, there are some marked changes. The little h following the letter represents a little puff of air that follows the sound — the difference between the “p” in “pet” and the “p” in “spot”. Interesting is that English lacks the standard /r/, or a rolled r, but rather has a /ɹ/, which is a very rare sound among the world’s languages. But there are far, far more sounds that exist beyond the scope of the meager few — relatively speaking — that exist in English.