Investigation: FUHSD and Sexual Assault

March 29, 2021

Introduction

In the past few years, Cupertino High School has been a host of numerous claims of sexual harassment. Many students have called for change through social media platforms, such as the #MeToo LGHS Instagram account, which had a popularity surge. There have been many sides to this argument. The administration believes it has done as much as it can to curb the problem. In contrast, students have a broad range of perspectives ranging from demanding that admin do more to siding with admin and understanding the difficulty of handling such shrouded cases with ambiguity.

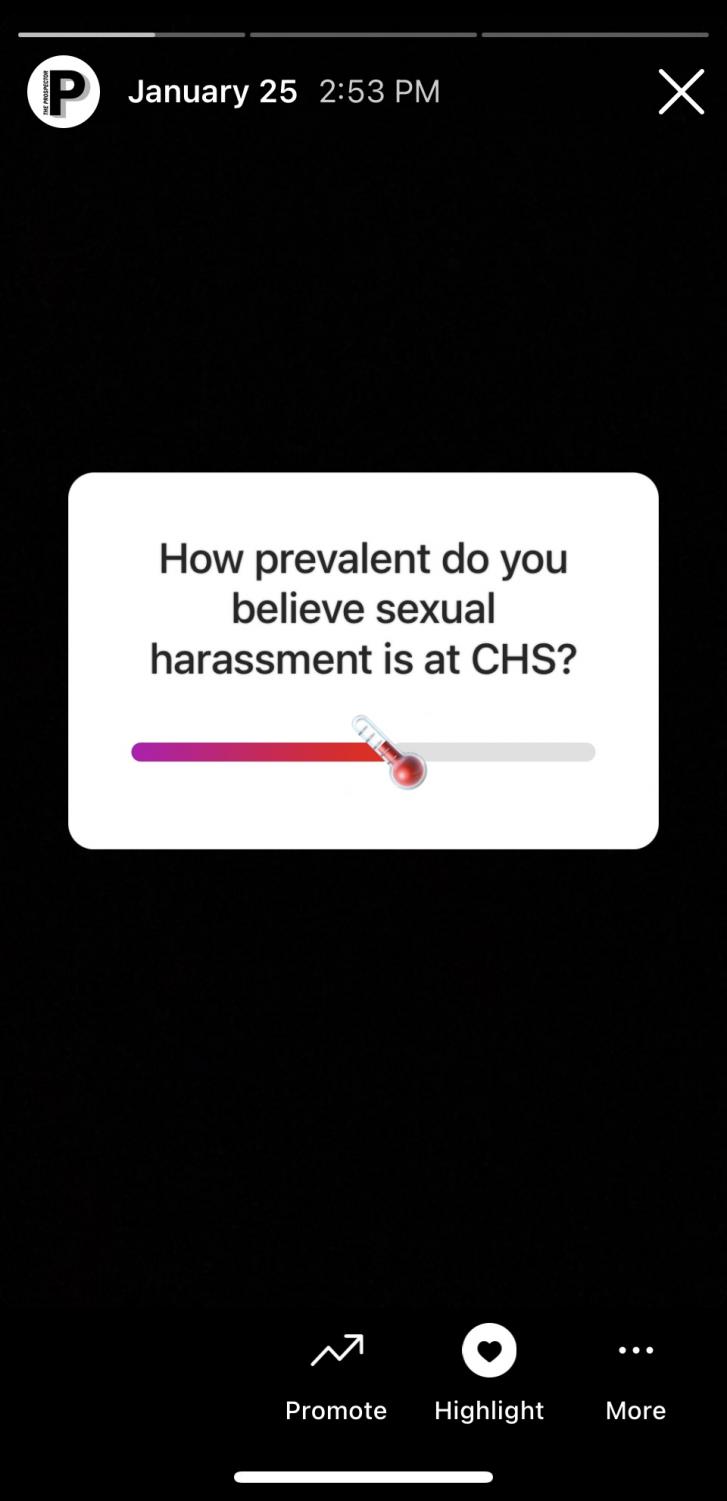

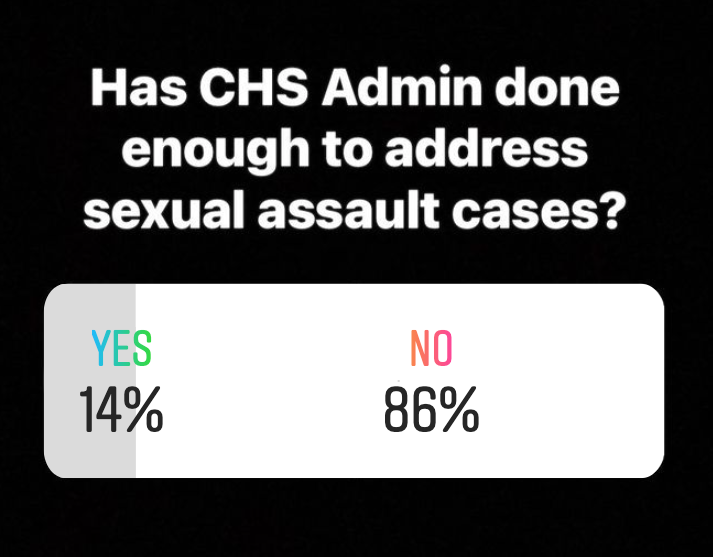

While there have been responses, several believe it is not enough. Only 13% of the student body surveyed believed that Cupertino High School’s administration has sufficiently addressed the threat of sexual harassment on campus. Despite these differences, there is an agreement that sexual harassment needs to be ended; the question that has the population divided is on whose shoulders does the responsibility fall?

Student Perspective 1

The Fremont Union High School District (FUHSD) has a controversial history of handling sexual assault allegations. Perhaps the most prominent example is the story of One, an FUHSD student who anonymously reported how the district handled her sexual assault case after she raised awareness for her case on Instagram. Another Cupertino High School senior, A, has also reported negative experiences.

The FUHSD administration team has been accused of being insensitive to students’ experiences. Said A, “I remember being blamed by the school admin the first time I had reported my experience. The admin asked me insensitive questions and comment like, ‘maybe you guys liked each other,’ ‘maybe you got the wrong idea,’ ‘did you like him?’”

Said One, “They didn’t ask if I wanted to meet with a counselor, they just called me in whenever they felt [it was] convenient and asked me to tell my story […] I was never really asked if I was comfortable sharing, but even if I had been, I was under the impression that this would all be worth it in the end […] but in the end nothing really happened and I lost more than I gained.”

She continued to describe the district’s unsupportiveness. Said she, “They seemed to take Two’s side. I never felt supported […] They never told me, ‘he’s done a bad thing and we’re going to help you.’”

She continued to describe the district’s insufficient intermediate action to help her cope with the event. “I went a few weeks retelling my story […], and the district didn’t decide to do anything. [They] contacted the teachers of the classes that I had with Two and they had them rearrange the seating chart, but that was the farthest they went […] Then my parents told them I had been diagnosed with autism at a young age, and then they decided that they should move Two out of my classes. […] Ultimately, they closed the case, and that was it.”

After she posted her story on Instagram, she realized the extent of the problem within the district. Said One, “I’ve gotten […] close to a hundred DM’s […] telling me their own stories. […] I didn’t know that there were that many other people, almost the much the same experience with the same district […] when students read my story, they feel this sympathy, and then they think, this shouldn’t happen to anyone, and I hope your story changes this for other people, so they really tend to look at the bigger picture, but when the district sees it, they thought it was a ‘me’ thing.”

View this post on Instagram

After One posted her story on Instagram, the district offered to reopen the case. But it wasn’t what One wanted. Said she, “it’s not about me, they think that if they can reopen my case and solve it, this would be done, but the fact is that they’ve done this to other people […] I’m giving this voice to everyone else who’s been through the same thing.”

According to these students, the district needs to do better. It needs to create policies where students don’t have to relive their traumatic experiences repeatedly and have sufficient circumstances while their case is open to provide them relief from their assaulter. Said A, “At CHS, the admin can do a better job communicating with their students, allowing outside survivors of sexual assault to share their stories, host events that can allow advocates for sexual assault come to talk to small groups.”

STUDENT PERSPECTIVE 2

An essential aspect of understanding cases of sexual harassment at Cupertino High School is understanding that several cases are never reported. Students often feel that the admin will not provide the support they want or want to forget about the incident. Another reason for students not alerting the admin about and incidence of sexual harassment is that they are dissuaded by their peers or other community members.

One student came forward and explained how her teacher suggested that she let them (the teacher) handle it rather than informing the admin. A former junior at CHS, E, gave an account of her experiences and how she felt her teacher did not take the necessary course of action.

Said E, “I was a TA … I was around this one troubled kid … one day I was grading papers and he comes up, and he first [touches] my ass. And then I was like, ‘What the heck are you doing,’ and he was like, ‘Oh it was accidental’ … this happened three more times, and the third time he smacked my ass… I felt really violated and threatened, and he was like, ‘Come on, just take a joke.’”

She explained that the teacher did not want the harasser to lose future career opportunities or disrupt his family life. “That’s why the teacher said, ‘Tell me next time and I’ll make sure you’re not around him,’ but proper action was not taken.”

E explains, “Justice, but not so that everybody knows, so then more people can actually come forward […] because you can only ensure that we’re safe within the walls, and once we go out, who knows if somebody is going to threaten us because we came forward. You need to impose rules like that.”

Instances such as this represent the vast number of cases of sexual assault that happen in this community but are never reported, so they go unnoticed.

E continued, “I think it’s a long process because there’s only so much a school can do. But it starts with keeping it very private. I think the major ones that come out, the school never intends on getting it out, or like with big police cars calling us in the middle of the day. As students, the office [is] so open. That’s why people don’t come forward.”

She continued to explain that students often feel afraid of the consequences of speaking up. Said she, “You never know what could happen in the hallways; you never know what could happen between the locker rooms. So, we can only get to that stage, if they keep it private, not everybody wants to be heard[…] because it could cause so many problems within their own household […] It’s not always about getting [the] word out, […] it’s also about keeping us safe and private.”

This is the epitome of the problem at Cupertino High School. There is a perpetual cycle of distrust and miscommunication amongst the school hierarchy’s various echelons, making it immensely more difficult to handle the situation. If the administration is not notified of a problem, they cannot take action, and even once they are alerted, there are legal barriers they are not allowed to cross. On the other hand, sexual harassment is a form of emotional trauma that requires clear communication and support, and according to victims, this has not been provided. Faculty are legally obliged to report sexual harassment. Still, at the same time, situations are rarely black and white, so they are put in a position that seems to have no positive outcome either way. According to victims, students have been excellent at raising awareness, but they have had a hard time opening their hearts and turning a listening ear. These aspects of triumphs and flaws in every demographic give a view into why sexual harassment has been prevalent and has hopefully provided the information needed to know how to eradicate it from the Cupertino community.

Administration Perspective

Victims have blamed administration for being insensitive and their overall disregard on these sensitive topics. On the other hand, there is no evidence that the admin has not adhered to legal requirements.

The two categories of sexual harassment often discussed at Cupertino High School are faculty to student harassment and student to student harassment. Both differ significantly in the implications and way in which they are handled.

When there is a claim of sexual harassment between a faculty member and a student, the administration is legally obligated to file a report with the police. There are no known cases in which this did not happen.

The more common type of sexual assault which several students believe is not adequately handled is student-to-student. One obfuscation that complicates student to student sexual harassment is when both the perpetrator and victim are minors. Therefore, they both fall under minor protection laws.

Said Cupertino High School Principal Kami Tomberlain,“We’ve investigated a number of claims over the years. I’ve been here thirteen years, and so it’s not unheard of for a young person to come forward and say, ‘this happened to me,’ and we take it very seriously.”

Principal Tomberlain explains that the administration always handles these cases with the necessary legal precautions and attempts to do the most that they can.

Said Tomberlain, “We investigate, we involve the police, we try to interview as many people that might have information to help us get the facts as possible. If we have cameras that might give us information, we utilize those. We take statements from the person who is claiming to be a victim, and we take statements from an individual who might be accused.”

However, even with all of these measures, the administration cannot always come to a conclusive end which can result in the victim feeling as though they were not given the justice they deserve.

Said Tomberlain, “We are unable to corroborate what happened. It doesn’t mean we don’t believe the person. I mean, there’s a difference between my gut believing what you’re telling me and being able to prove it.”

The admin’s inability to adequately bring justice to these survivors of sexual harassment points to a deeper problem – a systematic problem. The system in which survivors of sexual harassment report their experience is broken and leaves admin with their hands tied.

Some victims themselves have said that they believe the duty to fix the environment around sexual harassment at Cupertino no longer falls on the administration but rather the student body. Admin cannot rely solely on the student’s word, and when admin’s hands are tied, some victims seek help from other sources.

Victims look for their peers in the student body to empathize with them. They have mentioned that while many students are aware that sexual harassment is a severe problem, they choose to ignore these problems because it is difficult to hear and digest the stories of someone being violated. Victims often feel ostracized by the student body, leading to further consequences that they do not deserve. However, this is not the administration’s fault, but the fault of the student body.

Current senior and victim, A, explains that “[Many] student know how prevalent sexual [harassment] is; it happens to almost one out five women. But I don’t think it’s the number of students or the stats that matter. I think it’s the fact that we blame the victim themself and therefore, they are shut off.”

Despite advisory lessons and other attempts the administration has used to raise awareness, their influence is limited. Eventually this responsibility of changing this mindset of victim shaming falls onto the student body.

Said A, “There is a lot of shame around being [sexually harassed] and often that’s hard to talk about. ”

One solution that victims have suggested is having smaller group discussions in which victims can feel more comfortable sharing their stories. The student body can grasp the gravity of the situations their peers have dealt with.

Principal Tomberlain has voiced her agreement on this idea of smaller group discussions as well. She has a presentation solely based on avoiding sexual misconduct that she would like to introduce to the curriculum, and she would rather have it presented in a smaller group.

Said Tomberlain, “[The gym] just seems like a really odd place to be talking about this. I would like it to be a smaller group, so my preference would be to be able to do it on a block day and have people come through their English classes and do it, so it’s a smaller group.”

This need for more awareness and empathy After the resurgence of the “#MeToo” movement in 2016, America saw the conversation surrounding sexual harassment take a new form. A form that decided not solely to point to individuals who committed acts of sexual harassment but one where we were critical of and aimed to dismantle the inadequate system to help these victims. This same restructuring of the conversation surrounding sexual harassment needs to happen in Cupertino High School.