“The interesting thing about transplants, or at least the heart one, is that the nerve that connects your brain to your heart no longer functions. So your brain is not telling your heart, you’re beating too fast, or you’re beating too slowly. It doesn’t have that connection, [your body] has to learn the science.”

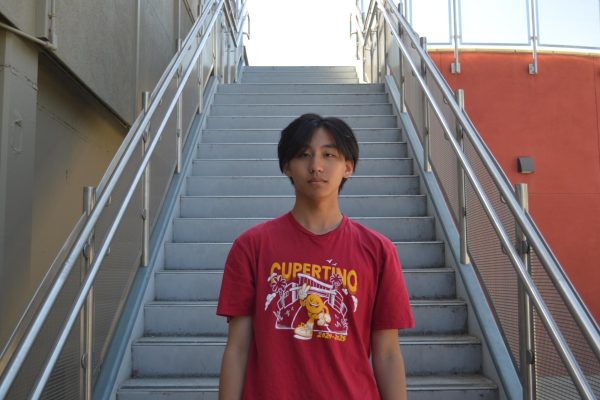

For Cupertino High School Spanish teacher Liza Aguilar, the process of learning her new heart’s rhythm has been routine since her heart transplant. In January 2010, Aguilar began working at Cupertino High School. Six years later, more than a decade after she started teaching, she was first diagnosed with cardiomyopathy.

The heart muscle disease affects one’s heart’s ability to pump blood into the rest of their body, potentially leading to heart failure.

“[My condition] was treated with medication until 2019 [when] it just got worse,” Aguilar said. “It got to the point where my body just couldn’t function on its own even with medication. And then that’s when I had my first surgery.”

In the surgery, a device designed to assist the heart in pumping blood was implanted into her body. Without it, the rest of her body couldn’t get the amount of oxygen and blood that it needed.

“That device was, I guess, life saving in the fact that it allowed me to continue with my job, with my daily life,” Aguilar said.

However, the device needed to be either powered by battery or through an outlet. “I had to limit a lot of activities because I was carrying around a backpack because I had a cable coming out of my abdomen that connected to the battery,” Aguilar said.

Aguilar continued to use this device into the COVID-19 lockdown, where she was able to teach remotely for the entire year. Digital learning made it much easier to avoid the setbacks of the device. Coming back from the pandemic, Aguilar began to realize its disadvantages.

Said Aguilar, “I was tired when I had the device because it got to the point where even that was kind of a struggle. And that’s why I ended up going on the transplant list because I knew that long term it wasn’t gonna help.”

“And that’s why I ended up going on the transplant list because I knew that long term it wasn’t gonna help.”

After a year on the transplant list, Aguilar received a call about an available donor. In November 2022 she underwent the procedure and successfully received a heart transplant.

Joy Keifer, Aguilar’s long-term substitute, came out of retirement to substitute for Aguilar throughout her medical complications.

“I feel very lucky that I’ve never needed a heart,” Keifer said. “It’s been tough for [Aguilar], and I wanted to share some of what I could with her. So I had promised her that when she got her heart transplant, that I would be there for her.”

At the start of the 2023-2024 school year, Aguilar returned from her leave. Other than having to take medication to prevent her body rejecting the organ, she has been allowed to return to her regular activities. Despite her autonomy, Aguilar is remaining cautious about her actions..

Said Aguilar, “I do everything I need to. I take my pills, I eat healthy, even though I could eat everything I want — I would never want to reverse my life in that way.”

Aguilar is currently in a rehabilitation period, where she attends classes to help with heart regulation.

Although it has been an adjustment for Aguilar to return to full-time teaching after years of working on and off, she is extremely grateful for her students’ understanding of the situation, and emphasizes the importance of resilience.

Said Aguilar, “I feel very fortunate, and I hope that I convey at least to my students, things come up, you can’t control things. But hopefully, you’re still positive in that it’s not the end of the world when something bad happens, because there might be a solution that you’re not even aware of.”