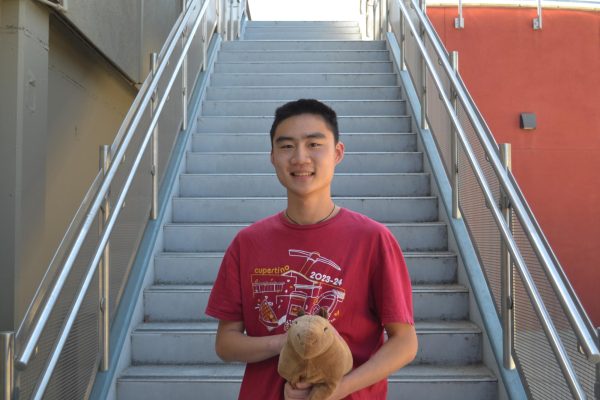

Sure enough, the audience demanded an encore. As senior and musician Ajinkya Ranade readied himself, calculations flashed through his head: 27 times three is 81, divided by eight is 10, ending on one. As he took a deep breath, his hands hovered over his favorite instrument, the tabla, and he prepared to produce a melody that had been heard nowhere else until then.

Ranade has played the tabla since he was six years old, when he heard some traditional music and was inspired to learn the percussion in the song. The improvised nature of the songs and mathematical nature of the beats, in patterns of eight with different rhythms to pick from, proved to be a challenging slope to climb.

He explained that he encountered a steep learning curve in the first two years, as it is more difficult to produce a satisfactory sound compared to western instruments like the violin.

“It takes a long time to create the clarity of your stroke. So when I first started, I was literally doing the same finger stroke for 30 minutes, one hour every day,” Ranade said, making drumming motions with his right hand. This repetition gave him patience later on in his life.

The tabla, an instrument common in traditional Hindustani music, consists of two drums, one bigger and lower-pitched — the Bayan — and one smaller and higher-pitched — the Dayan. Ranade explained that the techniques used in playing the tabla allow for a wide range of sounds to be replicated.

“[With] the combination of both of those [instruments], you can make a whole language of syllables. You can also speak the same rhythms out loud, and you can transfer information that way, or tell a story or imitate certain things. We have certain compositions, which are supposed to imitate railroad tracks on a railroad,” Ranade said.

Ranade places a large emphasis on storytelling through his music. His gigs range between playing with a small band and a larger ensemble with dance and song components, all of them coming together to convey a narrative. Whether it is a religious theme, a love story or a serious drama, the music always plays a key part.

Said Ranade, “If the singers sing softly, then [I play] softly. If the singer has lyrics that are about a girl […] or a god, you have to try to match that emotion.”

There is a teeming community of people interested in this music. Ranade has been invited to perform concerts in not only the Bay Area, but other cities and states, holding solo and accompaniment performances in Los Angeles, San Diego, Dallas, Houston, New York, New Jersey and even Calgary, Canada, along with complimentary room and board.

“Two weeks ago, our show had 450 [to] 500 people. […] But there’s also smaller concerts which happen in houses, so it’s a more intimate setting with only 45 [to] 50 people,” Ranade said.

Interestingly, Ranade’s musical language has connections to mathematics. One component of why the tabla is so difficult to master is its structure. There is minimal sheet music and each rhythm is improvised, in sets of eight beats. The typical structure of a tabla beat starts with a theme pattern, then goes through several variations before leaving on the same beat.

Ranade has also explored other forms of music by participating in concert band and choir. With the help of his choir teacher, Andrew Aron, he applied his tabla knowledge in his choir group, using the instrument as accompaniment to the songs. Now, it is a common accompaniment whenever his acapella group performs.

Being an avid percussionist, Ranade discovers rhythms in his daily life. “If we’re waiting at the light for a left turn, the blinkers are on. Oh, that’s a metronome,” Ranade said.

Ranade plans to continue his musical journey in the Bay Area, where the reception for classical Hindustani music is high. He plans to dig his roots deep and bring his skills to the next level. But whether it’s helping the choir group out with percussion or playing as a soloist to a sold-out venue, Ranade’s rhythms enrapture the attention of those around him.