The Harm in Queerbaiting

October 12, 2021

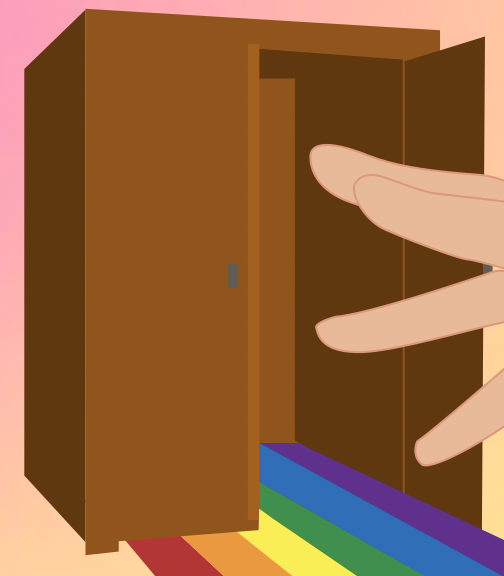

Queerbaiting: a term that uses a word that it does not represent. With a history spanning to the early 2000s, ‘queerbaiting’ was first coined and popularized by internet fandoms frustrated with the lack of genuine LGBTQIA+ representation in television shows. And while the term has stuck around in today’s generation, its meaning has since been used to describe a variety of circumstances where promises of LGBTQIA+ representation are not kept.

Even though it might seem obvious that using an identity that many identify with as a marketing tool is distasteful, there are many more reasons why queerbaiting is inappropriate and harmful. Not only does it lead young teens and children to believe that there is little representation on screen, but it can also enable corporations to profit from disingenuous marketing to the LGBTQ+ community.

Many popular shows and series have used queerbaiting as a tactic to rope in a larger audience, appealing to those of the LGBTQIA+ community to rake in monetary profit. Some well-known examples include Riverdale, Pitch Perfect and, debatably, The Legend of Korra, which featured an ending that left many viewers on the edge of their seats without any answers. While co-creator Bryan Konietzko later confirmed that the two female characters were indeed in a relationship, the ambiguous ending read as noncommittal to many modern fans.

“Because of the relative scarcity of queer relationships onscreen, the bait and switch can be especially harmful. Seeing queer representation on TV can be incredibly affirming to viewers. When that representation ends up being just for show, it can make you feel like your story isn’t important enough to be told—or even that it doesn’t exist,” digital media company PureWow editor Sarah Stiefvater said.

Seeing a character they can relate to onscreen helps those who are still questioning feel more represented. This is especially applicable to teens who are still unsure of their identity, especially those that may seek out movies and films to better understand themselves through a different lens. But by using this as a cheap marketing strategy and not as part of the character’s journey of discovery and growth, movies that queerbait quickly sever the connection between the viewer and character.

Said activist and filmmaker Leo Herrera to Rolling Stone, “[Media makers] play with our lack of representation and desires to get us in the theaters or get us to watch.”

In addition to letting down viewers with expectations of a relatable experience, queerbaiting boils down the heartfelt experiences of many into just another short-lived trend or quirky aesthetic.

An excellent example of this is during Pride Month. Many large companies pretend to care about pride and change their logos to sell products that seemingly support LGBTQIA+ businesses and causes, only to switch back once June ends.

“Companies, including H&M, donate a portion of what their customers spend on pride merchandise to LGBTQ charities. The amount going to charity varies by the company and product […] taken in aggregate, this consumerist donation structure creates a context of so-called slacktivism, giving brands and consumers alike a low-effort way to support social and political causes,” VOX Senior Culture Reporter Alex Abad-Santos said.

Even though this does not directly fit the definition of queerbaiting, the companies’ method of promising representation to appeal to a broader audience still applies.

Most of the time, such corporations use LGBTQIA+ color themes and symbols to promote products to their customers, benefiting from an identity that they do not actually care about. When the companies’ facade drops after just one month, it shows how fleeting genuine morale is regarding the advancement of rights for the LGBTQIA+ community and how prevalent their lack of commitment is to pushing for such progress. Queerbaiting is an easy way for such companies to earn brownie points for seeming charitable, exploiting many trying to support a good cause at the hands of selfish enterprises.

Said Stiefvater, “It’s also a way for media to appeal to potential queer consumers without alienating the parts of their audience that might be uncomfortable with queerness.”

Alongside spreading their influence to queer communities, the non-commital tactics that companies use ensure that they are losing any of their conservative customers as well. This reveals how queerbaiting undermines the true meaning of Pride Month, a month dedicated to the LGBTQIA+ community, into just a month where associations can use rainbows and colorful flags to make money at the expense of those who need representation the most.

Despite this, calling out supposed queerbaiting can be just as harmful.

Those who understand the effects of queerbaiting may feel inclined to call out others as they see it. However, because of the vast social media platforms and the broad audiences that come with them, content creators and artists who are either questioning or are part of the LGBTQIA+ community can face backlash for something that may seem like a queerbait.

The backlash is especially harmful to those using their online platforms to try and figure out their sexuality. The threat of backlash could force them to out themselves while they are still unsure, and because of the enormous spotlight that comes hand-in-hand with social media, the number of eyes judging them could grow to be millions of people.

There is a fine line between advocating for queer depiction and misusing it, one that results in the tragedy of queerbaiting. While one incorporates queer characters and messages in a way that accurately represents the LGBTQIA+ community, the other harms queer communities and uses stereotypical narratives void of any true meaning to benefit the greed of others.