The Struggles Of Being Academically Average

“Ugh, I got an A-,” said my classmate.

“You think that’s bad? I got a B+,” said another.

As I sat in my fifth-grade classroom staring at the C on my math test, I could not help but feel academically inferior. If As and Bs were deemed unsatisfactory, what about my grade?

Through countless comparisons with my classmates, I realized that students and parents perceived grades as life and death. Grades determined one’s self-worth and, for some, their parents’ approval and affection.

Contrary to the Bay Area’s cutthroat, competitive, straight-A academic blueprint, I was never considered gifted. I was average and sometimes below it.

Growing up, I never spent my afternoons at Kumon classes. Frankly, I found tutoring tedious and socially depriving. Since their parents forced them to attend, my friends were shocked by my choice not to participate in such after-school classes.

My peers judged my parents’ laid-back approach to monitoring my grades since they were not the typical ‘tiger parents.’ Some students even came to the erroneous conclusion that my parents did not care for my future.

Looking back, it was a blessing. My peers’ shocked reactions to learning that my parents entrusted me to manage schoolwork caused me to wonder — momentarily — whether they were correct.

I attended school to the best of my ability but still struggled through my primary and secondary school years. Sometimes I found the tests my friends deemed “super easy” relatively difficult. I was often puzzled by novels and would reread pages hoping I would understand the content.

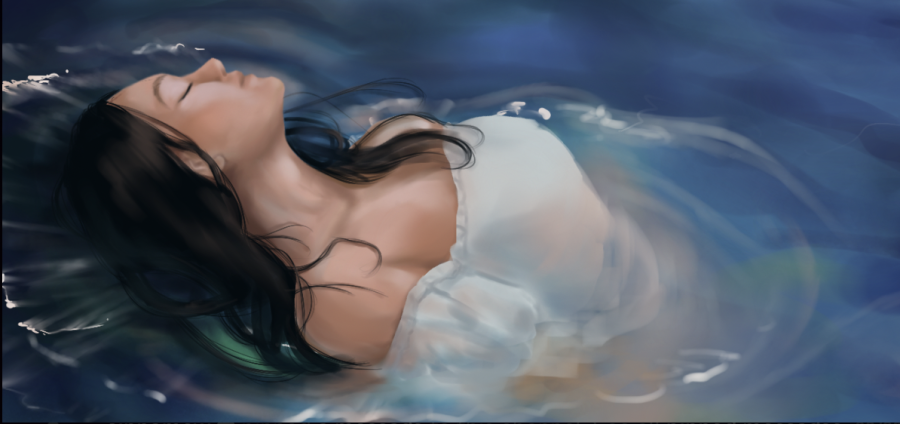

No matter how hard I tried, I continually felt my friends were years ahead of me in terms of education. My efforts were no match against those who spent their spare time polishing their skills at the Russian School of Mathematics. I was running a race where everyone crossed the finish line while I was tying my shoelaces.

Eventually, I became unmotivated to attend school, do my homework or obtain a tutor because I did not want to compromise my social well-being for assignments.

While continuing as a partially truant and nearly failing student — yes, near failing, not a B — the pandemic hit. While my academically-obsessed peers’ GPAs dropped, mine surprisingly increased.

With the first lockdown came social isolation, unless you loved texting, which I did not. “What did you do today?” with the response “I binge-watched Netflix” became exhaustingly repetitive conversations. Since I had hours of free time and could not meet other people, I had nothing else to do but schoolwork.

Under distance learning, I felt no academic pressure. The open-book exams and lengthy assignment deadlines created my ideal learning environment. My peers could not judge me through the screen, and my family was content with my grades, given that I put in the effort. I worked to become an above-average student, receiving a 4.0 GPA in ninth grade.

Although my grades eventually improved, I understood that was not the case for everyone. Given my experience with the temporary lack of academic judgment, I realized the implications of peer-inflicted standards.

There were frequent discussions on social media and with my classmates about ‘gifted kid burnout.’ Many expressed that being overworked at school had caused an academic decline in once-gifted students. Because of the emphasis on previously having good grades, society sympathized more towards burnout-induced academic struggles. Yet, academically average students did not experience the same courtesy from others.

Bay Area students’ attitudes do not grant struggling students understanding while doing so for the previously gifted — often leaving those in-between behind.

The inconsistent and ignorant standard that we all must strive for straight-As created a harsh divide between me and my peers. While burnout exists for the academically gifted, some students have never been gifted in the first place. Some of us are simply average, and that is okay.